Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society |

THE

BUILDING OF THE ERIE CANAL

by

Mary M. Root

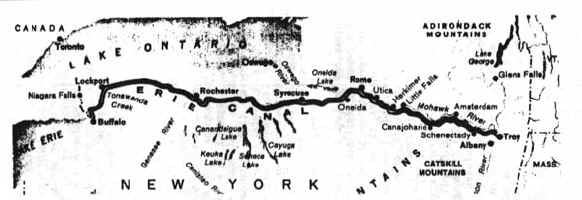

In 1816, the people of New

York City were worried about their economy. Baltimore and Philadelphia

were reaping the gains of the westward expansion. Their accessibility to

the Mississippi-Ohio river system via turnpike was the gateway to western

settlement. This was crucial. It was estimated that four horses

could pull one ton 12 miles a day over an ordinary road and 18 miles over a good

turnpike, but they could haul 100 tons 24 miles by water in the same period.

Speed and economy appealed to the settlers faced with moving their families and

possessions vast distances. New Yorkers mulled the problem over and 1817

approved the building of the Erie Canal from Albany to Buffalo.

The Erie project raised

the standards of canal-building, and was thus nicknamed the "Erie School of

Engineers". Many of the tools and methods they used were devised as

the work progressed. The men responsible for the design, layout and

execution of the canal were amateurs. Judge Benjamin Wright was appointed

chief engineer and James Geddes; a lawyer who had made a preliminary survey of

the canal's route, was named assistant chief. They drew about them a

number of very talented young people, among whom were John Sullivan, John

Jervis, Frederick Mills, Nathan Roberts and Canvass White. This group went

on to become the foremost canal-builders of the day. When they signed on,

they knew how to survey with the compass, level, and chain, but were in no sense

engineers. Profiting by experience, in a few years they were recognized as

the country's foremost hydraulic engineers.

Wright

and his assistants completed the survey of the Erie's route in the spring of

1817 and established the official length at 363 miles; the descent from Lake

Erie was measured at 555 feet. Two-way traffic was to be achieved by

installing eighty-three locks; twenty-seven of them in the first fifteen miles

between Albany and Schenectady around the Cohoes Falls. The work was to be

done using horses, mules, wagons, wheelbarrows, hand tools, and thousands of

Irish laborers. Wright

and his assistants completed the survey of the Erie's route in the spring of

1817 and established the official length at 363 miles; the descent from Lake

Erie was measured at 555 feet. Two-way traffic was to be achieved by

installing eighty-three locks; twenty-seven of them in the first fifteen miles

between Albany and Schenectady around the Cohoes Falls. The work was to be

done using horses, mules, wagons, wheelbarrows, hand tools, and thousands of

Irish laborers.

Ingenuity also played its

part. They invented the stump-puller, an ingenious device that enabled six

men and a team of horses to pull and remove thirty to forty stumps in a day.

Another timesaver they devised made it possible for one man to fell a tree by

attaching a cable to the top and winding it up on an endless screw.

Instead of wearing out a team bucking brush, they made the going easy by adding

a horizontal cutting bar to the plowshare. Work proceeded faster than

ever.

Canvass White had been

sent to England to study their canals and locks. When he returned, he

brought with him new instruments, a sheaf of carefully rendered drawings, and a

better knowledge of canal construction - especially locks - than any other man

in America possessed. Armed with this knowledge, the surveyors/engineers

were able to design and build locks, dams and bridges that were widely copied on

subsequent projects.

The work was completed in

1825. Cannons had been placed every ten miles along the route. To

signal the opening, they were fired in succession, taking eighty minutes to

traverse the route from Albany to New York City. Soon they would have even

greater cause to celebrate: the canal paid for itself within two years,

and brought prosperity to every town along its path. As a tribute to

Wright and his assistants it was written: "They have built the

longest canal in the world in the least time, with the least experience, for the

least money, and the greatest public benefit".

|