|

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

|

LOUISIANA

PURCHASE STATE PARK

By

Mike Trimble

Arkansas

Democrat Gazette

Sunday,

May 16, 1993

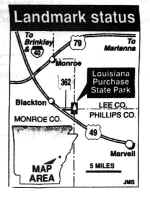

BLACKTON

- A Plain stone monument in a black-water swamp near this tiny Monroe County

community marks the origin of every township boundary, subdivision and property

line in all or part of 15 American states. BLACKTON

- A Plain stone monument in a black-water swamp near this tiny Monroe County

community marks the origin of every township boundary, subdivision and property

line in all or part of 15 American states.

It was from that spot, now a tiny,

isolated park, that a doughty band of bush bureaucrats led by Prospect K.

Robbins and Joseph C. Brown set out in 1815 to survey the vast wilderness that

had been obtained from France 12 years before in the transaction history knows

as the Louisiana Purchase.

Not surprisingly, the people who did it

have since sunk into the swamp of historical oblivion, while others, who led

flashier but less utile journeys, became fabled in song and legend.

Lewis and Clarke got all the ink;

Robbins and Brown got diddly.

Arkansas has done what it could over

the years to redress that injustice. An Arkansas chapter of the Daughters of the

American Revolution put the stone marker up in 1926, and the state Legislature

made the site a historic park in 1961. The little park has had its ups and downs

- lean budgets and neglect have occasionally left it less than accessible - but

its doing fine now.

And the federal government has finally

kicked in some recision, too. Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt announced

recently that the Louisiana Purchase Initial Survey Point Site - that's its

official name - had been designated a National Historic Landmark. That will mean

a plaque at the park, said Mark Christ, a spokesman for the Arkansas Historic

Preservation program, but it will also mean that the tiny park's status as an

undeveloped wilderness area now has federal recognition.

While the benefits of such recognition

tend to be symbolic rather than substantive, Christ says the federal designation

could prove valuable should the park ever be threatened by neglect or rapacious

development.

The Louisiana Purchase Historic State

Park marks the spot where Robbins and Brown began their survey of what was by

then known as the Missouri Territory. Their survey, ordered by President James

Madison, was but one chapter in a historic event that the late John Fleming, an

Arkansas newspaperman and historian, once described as the most bizarre real

estate deal in the history of the planet. In it, Napoleon Bonaparte of France

sold a huge mass of land he probably didn't own to a country that didn't want it

for more money than the country was willing to pay.

In 1803, the young United States of

America - Thomas Jefferson its president - desperately wanted to own the tiny

but strategically vital port of New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi

River. France owned the city, and also claimed title to the vast area to the

west and drained by the Mississippi. It had obtained that land from Spain in a

deal that Spain later contested.

Napoleon said the United States could

buy New Orleans, but it would also have to take the rest of the territory.

President Jefferson agreed to the purchase, though he wasn't sure he had the

power to do so.

History books teach that the territory

cost the United States $15 million, but incidental costs and interest rates

raised the final price to $27,267,622.

Oddly enough, the deal was financed

through a London bank at a time when the French and the English were at war.

Apparently, business was business, even in 1803, and there was the additional

fact that England, at that time, would rather have the United States than France

in possession of the port of New Orleans.

The War of 1812, in addition to proving

what terrible diplomatic seers the British were, finally necessitated a formal

survey of the lands of the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson had sent Meriwether

Lewis and William Clark trekking through the area in 1805, but theirs was an

exploration, not a survey - the same with a later trip by Zebulon Pike, of

Pike's Peak fame.

By 1815, however, veterans of the War

of 1812 were clamoring for some kind of bonus, and about the only thing the

government had plenty of was land. If the land could be surveyed, President

James Madison reasoned, it could then be opened to development, and meted out to

veterans as rewards for their service. The president commissioned Robbins and

Brown to lead the survey teams, and in August of 1815, the two men set out from

Washington by stagecoach, arriving in Arkansas by flatboat some weeks later.

Land surveys are conducted by first

setting a starting point. That's done by surveying a north-south line, called a

meridian, from a familiar landmark, and doing the same with an east-west line,

called a base line. Where those two lines intersect is the starting point of the

survey.

The lands east of the Mississippi had

already been surveyed, of course, and in the process, four meridians had been

established. Robbins and Brown split their men into two parties to establish the

two lines. Robbins established the Fifth Meridian by surveying due north from

the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers. Brown set out from the

mouth of the St. Francis River to survey the base line.

Both parties passed through extremely

rough territory, but their notebooks, which survive and are preserved at the

state land commissioner's office in Little Rock, reveal a stoic attitude toward

the hardships of the trek.

"This land would be good,"

reads one of Brown's entries, "if it were not subject to inundation."

That was a pretty mild description for

a man who was up to his waist in a swamp. Later, his patience possibly wearing

thin, Brown wrote in his notebook that the area which they were passing through

consisted of "briers and swamps and briers aplenty."

The two parties did not meet at the

point of intersection; that would have been a coincidence of epic proportions.

Each passed the intersection point sometime in November, and each party then

backtracked until they found each other some time between the dates of November

4 and November 24, 1815.

The two groups then determined the

point of intersection and hacked blaze marks in two gum trees to mark it.

From that point, the survey of the

Louisiana Purchase lands began, with the two imaginary lines extending as far as

the land itself. (Base Line Road in Little Rock is so named because it follows

the original base line laid down by Joseph Brown.)

All township boundaries were drawn from

lines that originated there, and from those, subdivisions and even city lots

were drawn. Before they were done, Robbins and Brown and their crews had

surveyed land in the future states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, North

Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska and Oklahoma - and most of five more - Kansas,

Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and Minnesota.

The initial survey point lay forgotten

for 126 years, which is a pretty long time unless you're in a black-water swamp.

Then, in 1921, there was a dispute

between Lee and Phillips counties over their common boundary line, which

happened to have been laid along the original base line of Robbins and Brown.

Two surveyors, E.P. Douglass and Tom Jacks, were hired to run a survey of the

line and clear up the controversy.

They did that, and they did something

else, too: They rediscovered the two gum trees slashed by Robbins and Brown in

1815.

Douglass, in a later interview with

John Fleming, recalled Jacks' exact words upon making the discovery: "By

all the odds of probability, this has to be the original point for the Louisiana

Purchase survey."

The L'Anguille chapter of the Daughters

of the American Revolution seized upon the rediscovery of the survey point as a

historical cause, and in 1926 they met at a temporarily dry site to dedicate a

stone monument.

The DAR had also obtained deeds from

landowners dedicating enough land for a small park at the site. They presented

the deeds to U.S. Senator Joe T. Robinson, who then began to deliver a speech.

Unfortunately, the late Senator

Robinson also began to stuff the deeds in his coat pocket, and they were never

heard from again. The loss of the deeds clouded the state's ownership of the

property for years. It was finally cleared up through legislative acts, and the

land was made a state park in 1961.

|