|

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

|

HADRIAN'S

WALL: THE ROMAN FRONTIER IN BRITAIN

by Mary M. Root

A wise military strategist, the Roman

Emperor Hadrian (117-138 A.D.) realized the futility of trying to subdue the

Celtic tribes. Successful Roman warfare depended upon a fight in open space,

where waves of infantry could pound the enemy mercilessly. The forested hills

and dales of Scotland favored Celtic guerrilla-tactics, especially ambush.

Hadrian selected the limits based on the land’s topography: Hadrian’s Wall

is a fortified boundary line.

Built in A.D. 122 by three Roman

Legions, the Wall with its fortifications linked a series of turrets, garrison

castles, and stationary, military camps along seventy-three miles of windswept

moor. The Wall hugged the north rim of the River Tyne, thereby commanding the

vicinity’s water supply and the hills above. Rather than Scottish forests,

Roman sentries instead controlled the bleak and desolate moor stretching between

the Irish and North Seas. The Roman surveyors and engineers traveling with

Hadrian established the Wall’s position, maximized the use of local materials

and talent in its speedy construction, and designed advantages for every Roman

defender. "In pursuing its course from sea to sea, the Wall seldom deviated

from the shortest and straightest course it could follow, and then only within

the evident design of seizing neighboring elevations that would have otherwise

commanded its position."¹

When first constructed, the Wall stood

about 15 feet high, 10 feet wide at the base and seven and one half feet wide at

the top. It is believed that an embattled parapet rose above the wall proper, to

protect sentries on patrol. To the north a short distance a ditch averaging 25

feet in width and 10 feet in depth strengthened the defense. To the south,

another ditch was created, with the excavated earth forming mounds along either

side. Today this ditch is known as the Vallum, although the Roman word means

"mound." The Vallum was the actual boundary line of Pax Romana

and the official limit of the Roman Empire, and as such, was probably

constructed first and used as an offset to the Wall, and for defense of the

construction crews.

Local availability of materials

counseled the Wall’s construction: stone was used for the 43-mile-long eastern

portion and earth was used on the remaining 30 miles to the west. The stone

blocks were generally 9 inches deep, 10 inches high, and ranged between 15 and

20 inches long. The stone faced an inner core composed of concrete and rubble.

The earthen portion was an early example of cut and fill engineering; the Wall

was formed with material excavated from the ditches.

It took three years to build the Wall

and its fortifications. This was accomplished by three of the mobile forces

known as a Legion. More than five thousand strong, a legion was an infantry

force organized into ten cohorts, nine of them numbering about 500 men each.

"The First Cohort was a special unit of almost double strength that

included fighting troops as well as specialists and clerks of the headquarters

staff. The ordinary cohort was subdivided into six centuries, or companies, each

of which contained about 80 men under the command of a career officer, the

centurian. Still smaller units were formed by the division of each century into

10 sections of eight men - contubernia, ‘tent parties,’ so called

because in the field they shared a leather tent. On the march, each contubernium

was provided with a mule, which carried the tent plus construction equipment.

According to first-century AD historian Josephus, this equipment included a saw,

a pickaxe, a sickle, a chain, a rope, a spade, and a large basket for moving

earth."² Every legion included a body of specialized soldiers known as

immunes; their skills earned them an immunity from routine duties. The list of

immunes included architects, surveyors, plumbers, medics, stonecutters, water

engineers, ditchers, blacksmiths and clerks. It took three years to build the Wall

and its fortifications. This was accomplished by three of the mobile forces

known as a Legion. More than five thousand strong, a legion was an infantry

force organized into ten cohorts, nine of them numbering about 500 men each.

"The First Cohort was a special unit of almost double strength that

included fighting troops as well as specialists and clerks of the headquarters

staff. The ordinary cohort was subdivided into six centuries, or companies, each

of which contained about 80 men under the command of a career officer, the

centurian. Still smaller units were formed by the division of each century into

10 sections of eight men - contubernia, ‘tent parties,’ so called

because in the field they shared a leather tent. On the march, each contubernium

was provided with a mule, which carried the tent plus construction equipment.

According to first-century AD historian Josephus, this equipment included a saw,

a pickaxe, a sickle, a chain, a rope, a spade, and a large basket for moving

earth."² Every legion included a body of specialized soldiers known as

immunes; their skills earned them an immunity from routine duties. The list of

immunes included architects, surveyors, plumbers, medics, stonecutters, water

engineers, ditchers, blacksmiths and clerks.

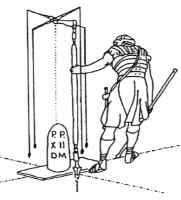

The military surveyors, known as

mensors, carried a Groma with them for laying out right angles, a

decempeda (a 10-foot rod) for measuring short distances, a waxed cord or

rope for measuring longer distances, a plumb line level known as a libra,

and writing and drawing materials. The mensors were responsible for the

overall position of the Wall, the stationing along its length of turrets,

mile-castles, and forts, and the interior layout of each fort. To establish

unerringly a line across Britain at just the point where the land was most

narrow was quite an achievement. It is thought that the Roman surveyors

performed the initial layout by lighting fires on hilltops, and "lining

themselves in" along the lowlands. Once the line of the wall was

established, the distances between structures were measured and marked. Turrets

occurred every 1600 feet. These were small stone towers, thought to have been

surrounded by wooden walkways. Turrets are sometimes referred to as signaling

stations, but it is not known what devices or codes the Roman sentries might

have been using. The "mile-castles"were established every 4,860 feet

(a Roman mile), and were square fortresses housing a garrison of 32 men. In

addition to patrolling the Wall, their duty was to protect the double gates that

marked a crossing point between "civilized" and "barbarian"

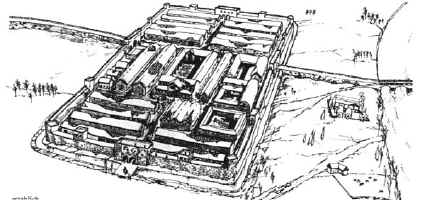

worlds. The stationary military camps were very large, and occurred along the

Wall approximately every four miles. Here the mensors laid out a rectangular

grid of streets, walkways and buildings. The layout was practical, military, and

predictable. Soldiers hailing from many parts of the Empire could orient

themselves wherever they found themselves stationed. The praetorium, or

headquarters, was centrally-located. Around it were grouped the quarters of

staff and bodyguard. Beyond this was a forum where the soldiers could meet, and

again behind this the quaestorium, or paymaster’s office. Adjoining

blocks contained the hospital, the foot-soldier’s barracks, kitchens,

storehouses and granaries, workshops, stables, and baths. Yes, even in this

remote outpost the Romans enjoyed the luxuries of plumbing. "There were

centrally heated communal baths as well as latrines. The toilets consisted of

wooden seats placed over a channel into which water could be poured to flush the

waste into a refuse ditch. In the baths, furnaces heated bronze boilers that

supplied steam and hot water. Besides cold or heated pools, the facilities

frequently offered a dry-heat sauna chamber and a steam bath. They were focal

points of the soldiers’ off-duty hours."³ There were other pastimes to

fill the lonely posting: archeologists have uncovered remnants of board-games,

drinking cups and flagons, letters written from home, and small shrines for

worship. The military surveyors, known as

mensors, carried a Groma with them for laying out right angles, a

decempeda (a 10-foot rod) for measuring short distances, a waxed cord or

rope for measuring longer distances, a plumb line level known as a libra,

and writing and drawing materials. The mensors were responsible for the

overall position of the Wall, the stationing along its length of turrets,

mile-castles, and forts, and the interior layout of each fort. To establish

unerringly a line across Britain at just the point where the land was most

narrow was quite an achievement. It is thought that the Roman surveyors

performed the initial layout by lighting fires on hilltops, and "lining

themselves in" along the lowlands. Once the line of the wall was

established, the distances between structures were measured and marked. Turrets

occurred every 1600 feet. These were small stone towers, thought to have been

surrounded by wooden walkways. Turrets are sometimes referred to as signaling

stations, but it is not known what devices or codes the Roman sentries might

have been using. The "mile-castles"were established every 4,860 feet

(a Roman mile), and were square fortresses housing a garrison of 32 men. In

addition to patrolling the Wall, their duty was to protect the double gates that

marked a crossing point between "civilized" and "barbarian"

worlds. The stationary military camps were very large, and occurred along the

Wall approximately every four miles. Here the mensors laid out a rectangular

grid of streets, walkways and buildings. The layout was practical, military, and

predictable. Soldiers hailing from many parts of the Empire could orient

themselves wherever they found themselves stationed. The praetorium, or

headquarters, was centrally-located. Around it were grouped the quarters of

staff and bodyguard. Beyond this was a forum where the soldiers could meet, and

again behind this the quaestorium, or paymaster’s office. Adjoining

blocks contained the hospital, the foot-soldier’s barracks, kitchens,

storehouses and granaries, workshops, stables, and baths. Yes, even in this

remote outpost the Romans enjoyed the luxuries of plumbing. "There were

centrally heated communal baths as well as latrines. The toilets consisted of

wooden seats placed over a channel into which water could be poured to flush the

waste into a refuse ditch. In the baths, furnaces heated bronze boilers that

supplied steam and hot water. Besides cold or heated pools, the facilities

frequently offered a dry-heat sauna chamber and a steam bath. They were focal

points of the soldiers’ off-duty hours."³ There were other pastimes to

fill the lonely posting: archeologists have uncovered remnants of board-games,

drinking cups and flagons, letters written from home, and small shrines for

worship.

The Legion surveyors were there to

physically define the legal boundary of the Roman Empire. Once delineated,

Hadrian’s Wall and fortifications represented the strength, stability and

comfort of being a Roman. The Wall was Emperor Hadrian’s strategic solution to

hostile terrain and intractable enemies. In time, he hoped to gain the northern

territories, but not by force; Hadrian believed that the prosperity, goods and

services of the Roman Empire would eventually accomplish more than its military

might.

Footnotes

¹The

Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th ed. (Philadelphia: J.M. Stoddart & Co.,

1880) p. 326.

²Charlotte

Anker, ed., Rome: Echoes of Imperial Glory, "Lost Civilization"

Series (Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books, 1994), p. 123.

³Ibid,

pp. 135-136.

Other

Reading

Birley,

Anthony R. Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Dilke,

O.A.W. The Roman Land Surveyors: An Introduction to the Agrimensores. New

York: Barnes & Noble, 1971.

Quenell,

Marjorie & C.H.B. Everyday Life in Roman and Anglo-Saxon Times. New

York: Dorset Press, 1959.

Reid,

T.R. "The World According To Rome," National Geographic Magazine,

Vol.192, No.2 (August 1997), 54-83.

|