|

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

|

Two

learned Romans, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, and Sextus Julius Frontinus, wrote of

surveying practices in the Roman Empire at the time of Christ. Undoubtedly

there were more works from their time, but many classical works were

irretrievably lost in the destruction of the Alexandrian library in 642 A.D.

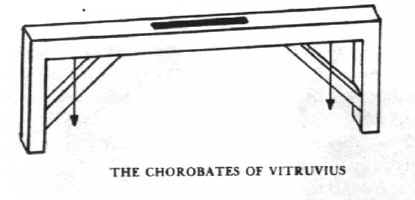

Marcus

Vitruvius Pollio, a master of architecture, presented De Architectura Libri

Decem (10 books) to this patron Augustus Caesar, about 20 B.C. Vitruvius

wrote of the CHOROBATES, an instrument used for leveling hydraulic gradients to

cities and houses. The water supply for Rome alone was comprised of ten

great a aqueducts, some coming from lakes as far as sixty miles from the city.

The CHOROBATES is described as a rod 20 feet long with duplicate legs attached

perpendicularly at each end. Diagonal pieces connect the rod and the legs,

and both diagonal members have vertical lines scriven into them, over which

plumb bobs are hung. When the instrument is in position, and the

plumb-lines strike both the scribe-lines alike, they show the instrument is

level. If the wind interferes with the plumb lines, the water level at the

top of the horizontal piece is used. Vitruvius instructs that the water

level groove was to be "five feel long, one digit wide, and a digit and a

half deep". By using two or more chorobates, established levelly, the

vertical distance between instruments could be established by sighting along the

depth of the uphill instrument, to a rod placed atop the lower chorobate. Marcus

Vitruvius Pollio, a master of architecture, presented De Architectura Libri

Decem (10 books) to this patron Augustus Caesar, about 20 B.C. Vitruvius

wrote of the CHOROBATES, an instrument used for leveling hydraulic gradients to

cities and houses. The water supply for Rome alone was comprised of ten

great a aqueducts, some coming from lakes as far as sixty miles from the city.

The CHOROBATES is described as a rod 20 feet long with duplicate legs attached

perpendicularly at each end. Diagonal pieces connect the rod and the legs,

and both diagonal members have vertical lines scriven into them, over which

plumb bobs are hung. When the instrument is in position, and the

plumb-lines strike both the scribe-lines alike, they show the instrument is

level. If the wind interferes with the plumb lines, the water level at the

top of the horizontal piece is used. Vitruvius instructs that the water

level groove was to be "five feel long, one digit wide, and a digit and a

half deep". By using two or more chorobates, established levelly, the

vertical distance between instruments could be established by sighting along the

depth of the uphill instrument, to a rod placed atop the lower chorobate.

Also in his writings, Vetruvius

describes a device handed down from the "ancients" for measuring

traveled distances by a counter fixed to the wheels of a chariot, similar to our

odometer.

Sextus

Julius Frontinus (c35-104 A.D.), a distinguished hydraulic engineer, authored De

Aqui Urbis Romae Libri II. It conveys in a clear and terse style much

valuable information on the manner in which ancient Rome was supplied with

water, and other engineering feats. He also made the distinctions clear

between the practices of the Roman "agrimensores" (field measurers)

and "gromatici" (GROMA users). The latter are named for the

favored aligning instrument of the Romans (handed down from the Egyptians

through the Greeks), resembling a surveyor's cross, that satisfied the bulk of

their requirements - laying out straight lines and right angles. The GROMA

consisted of a vertical iron staff (ferramentum) about 5 feet long, pointed at

the lower end, and with a cross arm, 10 inches long, pivoted at the top, which

supported the main aligning element - the revolving "stelleta" (star)

with arms about 3-1/2 feet across: The two main roads at right angles in a

Roman encampment were located by sighting beside the two plumb lines suspended

from the end of the cross arms to coincide with the central plumb line over the

selected central point. Areas of fields were measured by settling out two

right-angled lines, joining their extremities by straight lines and finding the

perpendicular offsets from these to the irregular sides. The metal parts

of the GROMA, as well as rods and other equipment, were discovered in the ruined

layers of Pompeii, in affirmation to Frontinus' descriptions. Sextus

Julius Frontinus (c35-104 A.D.), a distinguished hydraulic engineer, authored De

Aqui Urbis Romae Libri II. It conveys in a clear and terse style much

valuable information on the manner in which ancient Rome was supplied with

water, and other engineering feats. He also made the distinctions clear

between the practices of the Roman "agrimensores" (field measurers)

and "gromatici" (GROMA users). The latter are named for the

favored aligning instrument of the Romans (handed down from the Egyptians

through the Greeks), resembling a surveyor's cross, that satisfied the bulk of

their requirements - laying out straight lines and right angles. The GROMA

consisted of a vertical iron staff (ferramentum) about 5 feet long, pointed at

the lower end, and with a cross arm, 10 inches long, pivoted at the top, which

supported the main aligning element - the revolving "stelleta" (star)

with arms about 3-1/2 feet across: The two main roads at right angles in a

Roman encampment were located by sighting beside the two plumb lines suspended

from the end of the cross arms to coincide with the central plumb line over the

selected central point. Areas of fields were measured by settling out two

right-angled lines, joining their extremities by straight lines and finding the

perpendicular offsets from these to the irregular sides. The metal parts

of the GROMA, as well as rods and other equipment, were discovered in the ruined

layers of Pompeii, in affirmation to Frontinus' descriptions.

An inspection of Roman roads,

aqueducts, canals, buildings, city layouts, and land subdivisions confirms their

unexcelled proficiency in the use of crude surveying instruments as measured by

modern-day standards. Further inspection of archeological and written

evidence suggests the following points:

1. The range of Roman

instruments was restricted to the vision of the naked eye.

(Magnification by telescopic sights came in 1608).

2. There is no evidence of the

use of the compass.

3. Large scale maps were

greatly distorted in the E-W direction because the methods used for locating

relative latitude and longitude were not sufficiently accurate for

cartographical purposes.

4. Their entire astronomical

and geographical outlook was circumscribed by the idea of an earth-centered

universe and a rigid Euclidean geometry excellent for earth measurements but

elementary when projected into space. They understood a great deal of

algebra and trigonometry but very little calculus.

|