|

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

|

SURVEYING

PRACTICES IN EARLY SOUTH CAROLINA

by Louise Pettus

The English settlement of South Carolina dates back to 1670. Surveyors have

been involved and a part of South Carolina's growth and associated pains since.

In 1670, the streets of Charles Town settlement covered only nine acres and was

surrounded by water on three sides.

The English settlement of South Carolina dates back to 1670. Surveyors have

been involved and a part of South Carolina's growth and associated pains since.

In 1670, the streets of Charles Town settlement covered only nine acres and was

surrounded by water on three sides.

The Lords Proprietors, eight in number, received a grant of what is now North

and South Carolina from the King of England. An elaborate plan of government and

land settlement was worked out in England by the famous philosopher, John Locke.

For over forty years, the colonial surveyors, who worked out of Charles Town,

were affected by the decisions of the English philosopher who never set eyes on

Carolina.

The first settlers obtained title to the land only after going through a

cumbersome process. The settler would appear before the governor and the Council

to make a request for the land. The governor would then issue a warrant for the

land. The warrant was taken to the secretary who recorded it.

The warrant was an order to the surveyor general to make a plat of the land.

The surveyor general drew up a plat and a "return of survey". The

settler took these papers to the secretary who would check them against the

original record and then certify the plat. A copy of the certified plat was

recorded and the original plat was given to the prospective grantee. The

secretary then drew up a "sealed grant" which had to be taken to the

governor and to the council for their signatures.

Finally, the land grant was recorded in an official register. All of the

registration had to occur within ninety days of receiving the plat or the grant

was void.

Soon, the office of surveyor general could not keep up with drawing and

registration of plats. Short cuts were found. Abstracts replaced the original

lengthy warrants. The Council became tired of listening to petitions and

delegated that role to subordinates. The surveyor general subleased the

plat-making to deputy surveyors.

All fee schedules had to be posted in a prominent place. For nearly a

century, the fee for surveying one acre was a half penny sterling. Platting and

returning a survey was eleven shillings and eight pence and the running of old

lines for any person, or between parties, was fourteen shillings sterling per

day.

Nearly all of these original proprietary plats and returns of survey have

been lost. Only one volume, "Charles Town Lots, 1678-1756," and a few

isolated plats survive the early period. Fires, earthquakes, floods, and wars

have taken their toll. Because South Carolina was a royal colony, the abstracts

were sent to England and may be found in the British Public Record Office.

The first immigrants were allowed "headrights" which allowed the

settler to claim one hundred acres for himself, each member of his family,

servants, or slaves. Later, in order to encourage close settlement, headrights

were lowered to fifty acres per person.

When the proprietors lost control of the Carolinas in 1729, the crown took

over. The royal governor and the council, or upper house, were appointed by the

king but the assembly, or lower house, was elected by the colonists. The elected

assembly controlled the purse strings, a change of great magnitude.

With the shifts of governmental powers and responsibilities, there came

changes in the procedures of surveying, recording, and distributing land.

It became easy for speculators to gather up huge acreage. The assembly

ignored the old requirements for surveying and recording. It became the practice

to claim occupancy by merely cutting notches in boundary trees - a frontier

version of "Kilroy was here."

In 1732, Benjamin Whitaker, the surveyor general. wrote: "The law

enables any common surveyor to perpetuate frauds for his employers through not

having to turn his survey into any office." Whitaker's protests resulted in

his receiving a long term of imprisonment for contempt of the assembly.

Warrants were issued for about 600,000 acres in two years time. The governor,

himself, got 19,000 acres. The council voted themselves 6,000 acres apiece. The

land fever of 1731-1738 resulted in approximately one million acres being added

to the tax rolls.

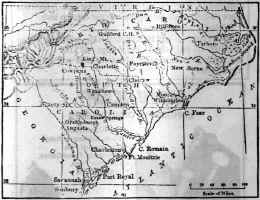

Meantime, the royal governors of North and South Carolina faced the problem

of running a boundary line between the two provinces. In 1730, after

correspondence with the crown, the two governors met and agreed on a line of

division.

The border line was to begin thirty miles south of the mouth of Cape Fear

River and to run north, at all times, of "Wackamaw" River. The line

was to run up to the 35th parallel of latitude and then due west, theoretically,

to the South Seas for that was the western boundary of Carolina as claimed by

England.

In 1734, three commissioners were chosen by the governor and council to run

the line. Not one of the three had any knowledge of surveying. They were

political appointments, and to make matters worse, the upper house had to ask

the assembly what they were willing to pay. The assembly replied that they would

not know until the commissioners returned.

At this point, Governor Robert Johnson stepped in with the advice that at

least one of the commissioners should have some knowledge of surveying and also

made the proposal that the commissioners receive a fixed compensation of five

pounds sterling per day.

The governor chided the two houses with the statement that it is "an

important matter to draw the boundarys of the two provinces." In case the

legislators missed his point on the seriousness of the matter, the governor

pointed out that, in case of dispute, the resultant maps would be sent to London

and examined by the Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations. The council

members, dependent upon the Lords Commissioners for their appointments, and the

assembly, dependent to a large degree on the London body for their treasury,

decided to follow the governor's advice.

Governor Johnson died before the survey party set out. The party carried with

it complicated and ambiguous instructions with so many "ifs" that

while they knew where to start, they did not really know where they were going.

The party was truly mapping unknown ground.

The surveyors returned in seven weeks "with Extraordinary fatigue

Running the said Line most of that time thro' Desart and uninhabited

woods..." The report describes having to clear obstacles and deal with

numerous rivers and "creaks", often felling large trees to make

crossing them possible.

The first survey party was defeated after a short distance and were replaced

by a second team. The second party got not much further and when it returned,

wrote a letter to the Council challenging the members to survey under the

conditions they had suffered for five pounds per diem. The surveyors had failed

to reach the 35th parallel.

The matter of the uncompleted North Carolina - South Carolina boundary line

rested until the end of the French and Indian Wars in 1763. The peace settlement

included the Treaty of Augusta which granted the Catawba Indians a tract of land

fifteen miles square. The 35th parallel would cut the Catawba lands in two.

The Catawbas requested that their reservation be laid off so that they would

have authority to remove the squatters and poachers who were increasing in great

numbers. The survey was made by Samuel Wyly, deputy surveyor, of Camden.

The question of whether the Catawba Indian land should be in North or South

Carolina was determined at a hearing in London. South Carolina's case was

improved by the Catawba's own request that they be connected to South Carolina.

Surveyors again tackled the task of continuing the old 1734-1736 line.

Through errors (intentional or not is not known), North Carolina surveyor, James

Cook, finally drew a line eleven miles south of "His Majesty's

intention." Confused, fatigued, and suffering from "the rains, the hot

weather and the insects", the surveyor stopped on the Camden - Salisbury

road, south of the Catawba lands.

Instead of latitude 35 degrees, the surveyors had run a course of 34 degrees

and 49 minutes. The error cost South Carolina 660 square miles of land.

The surveyors submitted a bill of 400 pounds sterling and a survey map which

Lieutenant-Governor Bull sent to London. Bull reminded the English government

that the Catawbas had originally complained that the North Carolina surveyor's

chains disturbed their stock of horses and cattle and that they had long served

the Charles Town government.

It was 1771 before the crown ordered the adjustment and the current South

Carolina - North Carolina boundary line was run around the Catawba Indian land

and then due west on the 35th parallel.

The Camden - Salisbury road became the eastern boundary of the Catawba

territory. It made an irregular and shifting boundary. When the British general,

Lord Cornwallis, tore up the road during the Revolution, a new road, now Highway

521, was cut.

With boundary change, many of the border residents were not certain in which

state they resided and often chose the one least likely to collect any taxes.

Finally, the two states agreed to settle the matter by choosing William

Richardson Davie, a native of South Carolina's Waxhaw settlement, but also a

former North Carolina governor and founder of the University of North Carolina,

to draw up a straight boundary line. Davie, who in retirement near Lands' Ford

in Chester County, headed the survey party that, in 1813, established a point

now known as "old North Corner" to mark the angle where the two states

join.

Reprinted from a booklet compiled and printed by Tri County Professional Land

Surveyors Association "With the permission of Winthrop College and the

Author Ms. Louise Pettus."