|

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

|

TACHEOMETER

by Wilfred Airy

Tacheometry, from the Greek "quick measure", is a system of rapid

surveying, by which the positions, both horizontal and vertical, of points on

the earth's surface relatively to one another are determined without using a

chain or tape or a separate leveling instrument. The ordinary methods of

surveying with a theodolite, chain, and leveling instrument are fairly

satisfactory when the ground is pretty clear of obstructions and not very

precipitous, but it becomes extremely cumbrous when the ground is much covered

with bush, or broken up by ravines. Chain measurements are then both slow and

liable to considerable error; the leveling, too, is carried on at great

disadvantage in point of speed, though without serious loss of accuracy. These

difficulties led to the introduction of tacheometry, in which, instead of a pole

formerly employed to mark a point, a staff similar to a level staff is used.

This is marked with heights from the foot, and is graduated according to the

form of tacheometer in use. The azimuth angle is determined as formerly. The

horizontal distance is inferred either from the vertical angle included between

two well-defined points on the staff and the known distance between them, or by

readings of the staff indicated by two fixed wires in the diaphragm of the

telescope. The difference of height is computed from the angle of depression or

elevation of a fixed point on the staff and the horizontal distance already

obtained. Thus all the measurements requisite to locate a point both vertically

and horizontally with reference to the point where the tacheometer is centered

are determined by an observer at the instrument without any assistance beyond

that of a man to hold the staff.

Tacheometry, from the Greek "quick measure", is a system of rapid

surveying, by which the positions, both horizontal and vertical, of points on

the earth's surface relatively to one another are determined without using a

chain or tape or a separate leveling instrument. The ordinary methods of

surveying with a theodolite, chain, and leveling instrument are fairly

satisfactory when the ground is pretty clear of obstructions and not very

precipitous, but it becomes extremely cumbrous when the ground is much covered

with bush, or broken up by ravines. Chain measurements are then both slow and

liable to considerable error; the leveling, too, is carried on at great

disadvantage in point of speed, though without serious loss of accuracy. These

difficulties led to the introduction of tacheometry, in which, instead of a pole

formerly employed to mark a point, a staff similar to a level staff is used.

This is marked with heights from the foot, and is graduated according to the

form of tacheometer in use. The azimuth angle is determined as formerly. The

horizontal distance is inferred either from the vertical angle included between

two well-defined points on the staff and the known distance between them, or by

readings of the staff indicated by two fixed wires in the diaphragm of the

telescope. The difference of height is computed from the angle of depression or

elevation of a fixed point on the staff and the horizontal distance already

obtained. Thus all the measurements requisite to locate a point both vertically

and horizontally with reference to the point where the tacheometer is centered

are determined by an observer at the instrument without any assistance beyond

that of a man to hold the staff.

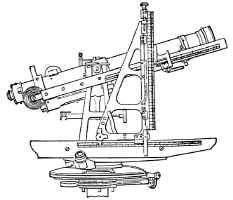

The inconvenience of the reduction work necessary to obtain the horizontal

and vertical distances produced the Wagner-Feunel tacheometer, by which the

distances can be read directly from the instrument. As is seen in the drawing,

three scales are provided, to measure the inclined distance, the horizontal

distance, and the vertical distance respectively. All three are arranged in a

plane parallel to the plane in which the telescope turns. The inclined scale is

attached to the telescope exactly parallel to its line of collimation, and moves

with it. The horizontal scale is fixed to the upper horizontal plate of the

theodolite. The vertical scale is on the vertical edge of a right-angled

triangle, which can be slid along on the top of the horizontal scale. The

inclined scale carries a slide which is provided with two verniers. One of these

is parallel to the inclined scale, and is for the purpose of setting off on the

scale (in terms of the divisions on the scale) the inclined distance of the

staff from the axis of rotation of the telescope. The other turns on a pivot

whose center is accurately in the edge of the inclined scale at the point where

the zero division of the inclined vernier cuts the edge, and is for the purpose

of reading the vertical scale; it can be turned on its pivot so as to be

vertical whatever may be the inclination of the telescope. Moreover, since the

distance from the center of the pivot to the zero of the vernier is always

constant and known, the vertical scale can be graduated so that the reading of

the vernier gives the height (in terms of the division on the scale) of the

staff above the axis of rotation of the telescope. The horizontal scale attached

to the horizontal plate of the theodolite is read by means of a vernier carried

by the triangle. To ascertain the horizontal and vertical distances of the point

on the staff which is cut by the middle wire in the diaphragm of the telescope

from the rotation axis of the telescope, the inclined distance of the point on

the staff is read by means of the wires. This distance (in terms of the

divisions) is then set off on the inclined scale by means of the inclined

vernier, and the vertical scale on the triangle is moved up to the vertical

vernier, which is adjusted to its edge. With proper graduation of the horizontal

and vertical scales the horizontal and vertical distances can be at once read

off on the scales. This method, however, requires that the staff be held so that

its face is perpendicular to the line of sight, which is more troublesome than

holding the staff vertical.

From "Tacheometry", The Encyclopedia Britannica. 11th Edition,

1911.