|

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

Article taken from "Backsights"

Magazine published by Surveyors Historical Society

|

From A Treatise on Land

Surveying, by W. M. Gillespie, New York 1870

Since a considerable field of view is

seen in looking through a Telescope, it is necessary to provide means for

directing the line of sight to the precise point which is to be

observed. This could be effected by placing a very fine point, such

as that of a needle, within the Telescope, at some place where it could be

distinctly seen. In practice this fine point is obtained by the

intersection of two very fine lines, placed in the common focus of the

object-glass and of the eye-piece. These lines are called the cross-hairs,

or cross-wires. Their intersection can be seen through the eye-piece, at

the same time, and apparently at the same place, as the image of the distant

object. The magnifying powers of the eye-piece will then detect the

slightest deviation from perfect coincidence. "This application of

the Telescope may be considered as completely annihilating that part of the

error of observation which might arise from an erroneous estimation of the

direction in which an object lies from the observer's eye, or from the center of

the instrument. It is, in fact, the grand source of all the precision of

modern Astronomy, without which all other refinements in instrumental

workmanship would thrown away." What Sir John Herschel here says of

its utility to Astronomy, is equally applicable to Surveying.

The imaginary line which passes through

the intersection of the cross-hairs and the optical center of the object-glass,

is called the line of collimation of the Telescope.*

The

cross-hairs are attached to a ring, or short thick tube of brass, placed within

the Telescope tube, through holes in which pass loosely four screws, whose

threads enter and take hold of the ring, behind or in front of the cross-hairs. The

cross-hairs are attached to a ring, or short thick tube of brass, placed within

the Telescope tube, through holes in which pass loosely four screws, whose

threads enter and take hold of the ring, behind or in front of the cross-hairs.

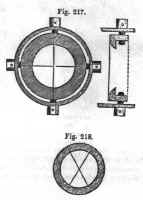

Usually, one cross-hair is horizontal,

and thother vertical as in Fig. 217, but sometimes they are arranged as in Fig.

218, which is thought to enable the object to be bisected with more

precision. A horizontal hair is sometimes added.

The

cross-hairs are best made of platinum wire, drawn out very fine by being

previously enclosed in a larger wire of silver, and the silver then removed by

nitric acid. Silk threads from a cocoon are sometimes used. Spiders'

threads are however, the most usual. If a cross-hair is broken, the ring

must be taken out by removing two opposite screws, and inserting a wire with a

screw cut on its end, or a stick of suitable size, into one of the holes thus

left open in the ring, it being turned sideways for that purpose, and then

removing the other screws. The spider's threads are then stretched across

the notches seen in the end of the ring, and are fastened by gum, or varnish, or

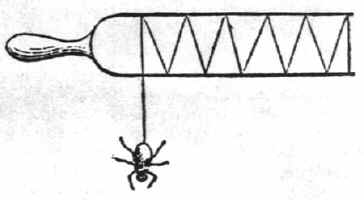

beeswax. The operation is a very delicate one. The following plan

has been employed. A piece of wire is bent, as in the figure, so as to

leave an opening a little wider than the ring of the cross-hairs. A cobweb

is chosen, at the end of which a spider is hanging, and its wound around the

bent wire, as in the figure, the weight of the insect keeping it tight and

stretching it ready to use, each part being made fast by gum, &c. When

a cross-hair is wanted, one of these is laid across the ring and there

attached. Another method is to draw the thread out of the spider,

persuading him to spin, if he sulks, by tossing him from hand to hand. A

stock of such threads must be obtained in warm weather for the winter's

wants. A piece of thin glass, with a horizontal and a vertical line etched

on it, may be made a substitute. The

cross-hairs are best made of platinum wire, drawn out very fine by being

previously enclosed in a larger wire of silver, and the silver then removed by

nitric acid. Silk threads from a cocoon are sometimes used. Spiders'

threads are however, the most usual. If a cross-hair is broken, the ring

must be taken out by removing two opposite screws, and inserting a wire with a

screw cut on its end, or a stick of suitable size, into one of the holes thus

left open in the ring, it being turned sideways for that purpose, and then

removing the other screws. The spider's threads are then stretched across

the notches seen in the end of the ring, and are fastened by gum, or varnish, or

beeswax. The operation is a very delicate one. The following plan

has been employed. A piece of wire is bent, as in the figure, so as to

leave an opening a little wider than the ring of the cross-hairs. A cobweb

is chosen, at the end of which a spider is hanging, and its wound around the

bent wire, as in the figure, the weight of the insect keeping it tight and

stretching it ready to use, each part being made fast by gum, &c. When

a cross-hair is wanted, one of these is laid across the ring and there

attached. Another method is to draw the thread out of the spider,

persuading him to spin, if he sulks, by tossing him from hand to hand. A

stock of such threads must be obtained in warm weather for the winter's

wants. A piece of thin glass, with a horizontal and a vertical line etched

on it, may be made a substitute.

* From the Latin work "collimo",

or "collineo", meaning to direct one thing towards another in a

straight line, or to aim at. The "line of aim" would express the

meaning.

|